Local health care workers demonstrated Thursday outside of Avante, a skilled nursing facility in Palm Beach County.

Continue readingUnthinkable — lawmakers give nursing homes a free pass, now look to cut quality of care: Jeff Johnson, AARP Florida State Director

Thanks to COVID-19, this Session of the Florida Legislature looks and sounds different.

Thanks to COVID-19, this Session of the Florida Legislature looks and sounds different.

With social distancing, online testimony, and streaming committee meetings, the Florida Capitol seems quiet, compared to past sessions.

And, as is true in so many horror movies, the quiet is foreboding.

Just as nursing home residents were victimized by the invisible coronavirus during the lockdown of the last year, so they are being victimized by the heavy-hitting industry lobbyists for nursing homes and health care executives in the locked-down Capitol.

Not only have lawmakers fast-tracked bills that give nursing homes immunity from COVID-19-related lawsuits (SB 72), now they’re fast-tracking cuts to the quality of care in Florida nursing homes. Letting these facilities off the hook by making it nearly impossible for residents and families to seek resolution through the court system is shameful.

Piling on proposals that cut the quality of care for nursing home residents is unthinkable — proof that the industry’s self-serving, aggressive push for less accountability and more profit is being fulfilled at the expense of resident safety.

Currently, nursing home residents receive most of their care from Certified Nursing Assistants (CNAs), who are required to have 120 hours of training before being certified. Two bills in the Florida Legislature by Northeast Florida legislators (SB 1132/HB 485), would allow nursing homes to substitute Personal Care Attendants (PCAs), who only receive 16 hours of classroom training and no mandatory directly supervised clinical experience, for CNA care.

While industry lobbyists have sold legislators the line that this is an apprenticeship program, they have made it clear that their real intent is to substitute lower-cost, lesser-trained PCAs for more qualified caregivers.

AARP continues to believe that PCAs should be able to supplement CNA care, but should not be able to substitute for CNA care. Unless the requirements for PCA trainees align with the level of training and supervision that current CNA trainees must meet before they serve on the floor of Florida nursing homes, residents will be at risk of poor care from undertrained staff.

We all know that the pandemic has put a spotlight on the difficulty nursing homes have to attract and retain CNAs for employment.

What the nursing home industry operators and executives choose to keep in the shadows is their failure to adequately pay and to provide benefits to CNAs. Most nursing home CNAs are paid less than what many people pay their pet sitters. Yet, anyone who has been in a nursing home knows that the CNAs are the heart of nursing care. Rather than push for fair pay for this challenging and essential CNA work, Florida is positioned to allow poorly trained substitutes to take their place

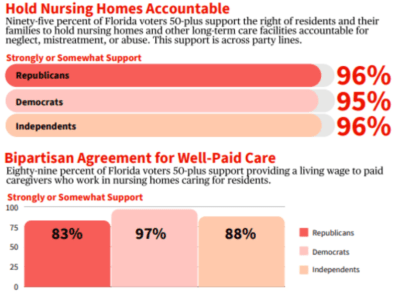

It’s not just AARP Florida that believes quality care for nursing home residents is essential. A new AARP report shows overwhelming bipartisan voter agreement (96%) that quality of care for nursing home residents is extremely or very important.

Additionally, 71% of Florida voters oppose replacing CNAs with lesser-trained PCAs in nursing homes, and 80% strongly support providing a living wage to paid staff who care for nursing home residents.

Let’s be clear: replacing CNAs with PCAs is a bad idea and it ignores the will of Florida residents.

It is no coincidence that Floridians hesitate or refuse to put themselves, family members or loved ones into Florida’s nursing homes. Even before the pandemic, Floridians have far preferred to age at home rather than in nursing homes; the combination of isolation and infection wrought by COVID-19 has only made that preference more pronounced.

Retiring in Florida should come with a warning label.

Florida’s policymakers and for-profit and not-for-profit nursing homes should learn from the past year and act on changes that would help our older loved ones receive the best care possible. Instead, they are delivering nothing but a gut punch to long-term care residents and their families.

With 11,000+ resident and staff deaths in Florida’s long-term care facilities due to the pandemic, it is unconscionable that Florida’s lawmakers are focusing on the welfare of nursing home operators and executives rather than the care and well-being of residents.

___

Jeff Johnson is the state director of AARP Florida.

COVID-19 Bills Would Protect Florida Nursing Homes From Neglect Lawsuits, Opponents Say

TWO BILLS BEING CONSIDERED BY FLORIDA LAWMAKERS WOULD MAKE IT HARDER FOR PEOPLE TO SUE HEALTH CARE PROVIDERS IN COVID-19-RELATED CASES. OPPONENTS SAY NURSING HOMES SHOULD BE HELD ACCOUNTABLE.

WLRN, Wednesday, March 10, 2021 by Jacob Wentz (WUSF)

AARP Florida is pressing members of the Legislature to oppose two bills that would grant health care providers some immunity from COVID-19-related lawsuits.

The bills, first introduced by Sen. Jeff Brandes, R-St. Petersburg, would protect health care providers from lawsuits over abuse, neglect and financial exploitation, said Jack McCray, advocacy manager for AARP.

Health care providers covered under the proposed bills include nursing homes, assisted living facilities, hospitals and other facilities defined by the state.

But opponents argue nursing homes and long-term care facilities should not be included in the civil liability protections because the institutions have historically required significant reform in the face of abuse.

“Florida’s procedures for negligence actions in nursing homes are already among the most difficult and complicated to maneuver in the country,” McCray said. “They are among the most vulnerable residents in the state of Florida. Negligence or exploitation in any form is unacceptable in a nursing home.”

More than 10,700 residents and staff of long-term care facilities have died in Florida due to complications from COVID-19. That’s 33 percent of Florida’s overall death toll from the virus.

Proponents say the state should shield health care providers from unnecessary lawsuits, citing structural and logistical challenges, such as staffing, that goes beyond the control of the institutions.

But opponents argue the bills (House Bill 7005 and Senate Bill 74) would make it harder for mistreated patients to hold health care providers accountable.

“So far the focus has been on the welfare of the industry and not the welfare of the nursing home residents,” McCray said. “Clearly this legislation is being promoted by the nursing home industry. If nursing homes are doing the right thing, they shouldn’t have to worry about it.”

Across party lines, Florida voters 50-plus support the right of residents to hold nursing homes accountable for neglect, mistreatment or abuse.

The AARP surveyed 1,000 Florida registered voters over 50 and found that 95% of respondents support the right of residents and their families to hold nursing homes and other long-term care facilities accountable for neglect, mistreatment or abuse. The support was the same across party lines, the survey found.

“So this really should not be a political issue, this should be an issue of quality care,” McCray said.

The AARP supports measures that would lead to quality improvements at long-term care facilities, such as adequate staffing and increased pay for employees. Providing more oversight at these facilities would also improve care, McCray said.

“This year, we have encouraged the legislature that this is an opportunity to really take a look and to develop a blueprint for the future of long-term care in Florida — one that’s going to bring long-term care out of the shadows into the sunshine,” McCray said. “There are countless things that can be done and that’s where the focus ought to be, not on civil liability immunity.”

WINK NEWS: Is a COVID-19 cover-up leading to case spread at a Fort Myers nursing home?

Reporter: Lauren Sweeney

Workers from Heritage Park Rehabilitation and Healthcare, who wished to remain anonymous, told WINK News that they are not being informed about possible infections of COVID-19 at the facility.

“We are walking into a room, not knowing if that person is positive or negative,” said one staff member.

According to a report published Wednesday from the Florida Department of Health, 26 staff at the facility are currently positive with COVID-19.

The same report showed that 13 residents with the virus were “transferred out” and no one residing at the Heritage Park facility in Fort Myers currently has the virus.

However, staff members told WINK News they fear that the case count is not accurate because the facility is no longer testing residents.

“At one point in time when they had a COVID-19 isolation unit, they were taking protocols to control spread by keeping it with the same staff,” said another staff member who also wished to remain anonymous.

In July, workers said management boasted the facility was “COVID-Free”.

But, a WINK News analysis of archived Department of Health case reports found a discrepancy.

From June 30, through July 7, the facility did not provide any updated case numbers to the Department of Health. Each day in that timeframe lists the reporting information from June 30.

Then, on July 9, when updated information is available, the number of positive residents dropped from 28 to 1.

The Department of Health and AHCA did not address questions about the apparent discrepancies found in case reporting.

AHCA said facilities report their own COVID-19 case information but failed to address follow up questions.

An executive order signed by Governor Ron Desantis in June required bi-weekly COVID-19 testing of all nursing home staff statewide.

The state does not require facilities to test residents routinely.

These recent worker concerns come months after the nation’s largest healthcare workers union filed complaints with state and federal regulators about safety concerns at Heritage Park.

WINK News first reported in May worker concerns regarding protective equipment and notification about patient’s COVID-19 status.

A worker in May said the staff only found out about the facility’s positive residents after looking at the Department of Health data online.

“I don’t like watching people get sick I don’t like watching people die,” said Damien Dixon, a resident at Heritage Park who said he had to sneak away from administrators to call WINK News.

According to Dixon, the quality of patient care at the facility has declined since the beginning of the pandemic.

In late May, the Agency for Healthcare administration found several deficiencies at Heritage Park related to COVID-19.

MORE: Find COVID-19 cases at long-term care facilities

Masks, gowns and other protective equipment were not readily available according to the report.

Inspectors also found two isolation rooms without signage to alert staff that it was isolation room or provide any information about why the patient was isolated.

COVID-19 positive residents are supposed to be in isolation rooms according to CDC guidelines.

In July, inspectors returned to find, “The facility failed to thoroughly evaluate resident’s needs and update the facility assessment to identify resources to provide necessary care and services to residents affected with the Novel COVID-19.”

Heritage Park reported to AHCA after the May and June inspections, that it would take corrective action.

AHCA has not answered WINK News inquiries on whether or not the facility is now in compliance.

Workers claim the problems still exist, and administrators are only interested in clearing the deficiencies so they can admit patients again.

“We can’t admit anybody because we have to clear our tags, because when you don’t admit anybody, that means the building’s not making any money,” said a staff member.

Consulate Healthcare, the company that owns Heritage Park, did not respond to several inquiries from WINK News.

Reuters: Florida’s Care Workers Battle to Protect the Elderly

BY ZACHARY FAGENSON AND LYNSEY WEATHERSPOON 17 AUGUST 2020

No place seems safe for Elonda English, not even her car.

Just after sunrise on a recent Wednesday she emerged from an overnight shift at the Lake Mary Health and Rehabilitation Center, a nursing home about 30 minutes north of Orlando, wearing a surgical mask and a condensation-fogged face shield.

In a parking lot surrounded by oak trees with billowing Spanish moss she pulled out what she calls her COVID bag, stuffed with an arsenal of sanitizers, from the trunk of her silver Kia Forte.

After slipping off her sneakers and spraying them down with disinfectant, she misted her feet, sandals, and her still-clothed body as she got into her car and pulled off her mask, waving at other masked nurses arriving for the day shift.

At her home in a small gated development of beige and dark green stucco townhouses and apartments, she’s greeted by a plaque outside of her front door.

The words of Psalm 91 are printed on a posterboard with an American flag, renamed the “2020 COVID Prayer of Protection.”

Inside, her 50-year-old mother Evelena Campbell, who drives a bus for another nearby nursing home, has been quarantined for the past week after testing positive for the coronavirus.

English, 35, a certified nursing assistant (CNA), is one of tens of thousands of elder care workers across Florida who for months have shouldered much of the weight and some of the losses of a growing pandemic that lingers across the peninsula, infecting more than a half a million people and killing nearly 9,000 others.

While much of the focus has been on doctors and nurses working in intensive care units, particularly in hard-hit South Florida, nurses caring for the elderly in places like Central Florida, with its massive retiree population, have long struggled for better pay, benefits and staffing levels.

“We are the foundation, and when your foundation has a crack in it you know it’s going to fall,” English told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

“I would say of the facilities that we represent 95% (of the CNAs) are females and I would say a good 60% of those are African-Americans and 30% are Haitian-American,” said Clara Smith, central Florida regional director for 1199 SEIU United Healthcare Workers East labor union.

In Smith’s region, the union represents about 15,000 workers spread across 76 nursing homes and similar facilities.

About 1,200 of those work for Consulate Health Care, the owner of the Lake Mary facility and the predominant nursing home company in the state.

So far one staff member has tested positive for COVID-19 at the Lady Mary Health center.

The pay across the industry is paltry.

Smith said the starting rate is $10.40 per hour in line with a four-year-old bargaining agreement. Most CNAs in the union make between $11 and $12 per hour. The state’s minimum hourly wage is $8.56, by law.

They’re offered health care insurance, but most don’t take it due to the high cost of premiums and deductibles.

The pandemic exacerbated the pay issues after nurses and other workers began falling sick and were forced to quarantine, sometimes more than once.

In some cases they were told they would have to use their vacation time, and the union is fighting with many companies for added hazard pay.

Smith said the union was able to file complaints with the federal government’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration and have those orders removed and the facility administrators replaced, but it’s still happening in some places.

Laura Gee, a 65-year-old CNA, who works at the Rosewood Health and Rehabilitation Center on the outskirts of Orlando, had to take time off work after experiencing symptoms similar to those in people suffering from COVID-19.

Gee was quarantined for eight days before testing negative and returning to work.

Prior, she was working up to 75 hours a week, and sometimes 100 after other nurses fell ill and couldn’t work.

Despite the low pay, the danger and the fact that Gee is diabetic and was hospitalized three times before the pandemic with respiratory issues, she said she and other CNAs remain committed to their patients, no matter the situation.

“The higher-up people can be kind of hard on us, we’re tired, we’re drained, we walk around like zombies and it’s only the residents that make us feel appreciated,” said Gee.

“I’m there for my residents and that’s how I keep going. I’m not there to please the administration, the nurses, or the head honchos. I’m there to take care of my residents, to make sure they’re clean and happy and to give them love.”

About one in five Florida residents is a senior aged 65 or older. Statewide there were about 140,000 residents and about 196,000 staff in assisted living facilities and skilled nursing facilities, according to the Florida Department of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Administration.

Of those 5,317 residents and 5,442 staff were positive for COVID-19 as of August 11. Those figures don’t include individuals who either died or recovered from the disease.

Brian Fox, head of the national nursing home watchdog group Families For Better Care, said the tragedy has been years in the making due to a growing trend of investment groups setting their sights on senior care and a failure of state and federal governments to provide adequate testing, guidance and safety equipment for nursing home workers at the onset of the virus.

“The bottom line took precedence over care and quality, and across Florida they scaled back on the one thing that costs them so much and that’s the labor costs,” Fox told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

A group of university researchers earlier this year released a study examining how private equity firms’ investments in nursing home companies have affected residents and employees.

Funds have been moving aggressively into the space nationwide over the last two decades. In 2004 there were 600 private equity deals for nursing homes. This hit 1,500 in 2019.

Among the findings were that acquisitions associated with private equity firms led to less money being spent on staffing and higher resident density, all leading to a lower quality of care as determined by the government’s five-star rating system for nursing homes.

“We expect that private equity-owned nursing homes would be less prepared in an emergency situation like this,” said lead researcher Atul Gupta, an assistant professor in the department of health care management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Consulate Health Care, owned by Atlanta-based private equity firm Formation Capital, has in recent years come under fire for everything from poor care leading to patients’ deaths to overcharging government programs for medically unnecessary treatments.

Consulate is the largest nursing home operator in Florida and the sixth largest in the country. Congress in June began investigating it and four other of the nation’s largest, for-profit healthcare providers over its handling over the novel coronavirus.

A statement from Consulate said the company had maintained a “vigilant focus” on protecting patients, staff and families since the onset of COVID-19 and its rates of infection, hospitalizations and deaths were better than national averages.

It had also given iPads to each center for families to stay in touch, provided bonuses to front line caregivers, compassion pay, and paid for COVID testing, among other measures.

“We have remained steadfast in our commitment to care for, and protect, our residents and staff during this unprecedented time and will continue to do so with compassion and vigilance,” the company said in a statement.

At English’s nursing home, she said workers were given disposable face masks at the beginning of the pandemic and told to make them last for 30 days. That dropped to 20 days after the union intervened.

Many are concerned about Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ recently announced plans to begin exploring how to reopen the state’s nursing homes to visitors, particularly the families of those residents who have been locked out since early March.

“I think a lot of the family members understand that these are difficult circumstances,” DeSantis said during a coronavirus press conference earlier this month in Jacksonville.

“Clearly they would not want policies to be done that would lead to massive amounts of people in these facilities getting infected. But I think that if you have a way forward, I think that would put a lot of people at ease, knowing that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Critics, however, are concerned that such a plan, without quick accurate testing, poses a massive risk for the already suffering industry and those living and working in it.

Whether that happens English still has procedures in place to minimize her risk of bringing the virus home from her job, or going out and getting exposed.

She’s constantly sanitizing every surface of her home and all but stopped leaving her house for anything other than the essentials.

“Things just aren’t the same anymore,” she said while in her kitchen preparing food for the workday ahead.

“You can’t enjoy life like you used to, you can’t go to restaurants, and now you almost have to be suspicious of everyone because you don’t know what people are doing and some people don’t even want to wear their mask.”

As she put on her mask she double checked her cooler bag. She brings her own plastic utensils, her own water, and food that won’t need to be reheated.

Even her insulin is sequestered. She packs it with ice into a small vacuum bottle before heading out the door with every day looking more and more like an endless unknown.

Tampa Bay Times – Letter to the Editor: Restore staffing levels

January 18, 2012

As a nursing home caregiver, I was deeply saddened when I learned of this heartbreaking death, which could have been prevented. This was a tragic end to the life of an elderly woman whose care was in the hands of others. These are the types of accidents that can take place when patient loads are too high and caregivers are pulled in too many directions at once.

Last year, staffing levels were cut and, as a result, the health and safety of nursing home residents are at risk. We must restore staffing levels. Our elders deserve to be protected from harm and to live their lives out with dignity.

Jean Berg, CNA, Hudson

Original Letter Available Here:

Tampa Tribune – Letter to the Editor: Hear our voices

November 7, 2011

During this special observance of Residents’ Rights Month, we must stand up and speak for those who cannot speak for themselves. Why can’t they speak? They are lying in beds — often alone and weak. Many do not have family members to come and take them outside to breathe in the fresh air. They are our seniors, and due to budget cuts to health care, they are receiving less bedside care. I know because I am a certified nurse assistant.

My joy in life is to make my patients smile. We owe it to them to speak up on their behalf and encourage nursing home administrators and lawmakers to make safe staffing levels a priority.

Cynthia Wilson – CNA

Tampa

Original Letter Available Here:

Tallahassee Democrat – Letter to the Editor: Make staffing levels a nursing home priority

September 18, 2011

With the severe budget cuts to Florida’s health care programs, our seniors have truly paid the price.

The reports of abuse, neglect and increased rates of infection in our nursing homes and assisted living facilities are daunting. We are pleased to see that there will be efforts to improve oversight, especially with the heavy patient loads health care workers are carrying.

Inadequate staffing levels can lead to senseless pain and suffering. Safe staffing levels must be a priority to ensure residents have enough bedside care to have some level of quality in their final years of life.

Our seniors deserve at least that much.

BARBARA A. DEVANE

badevane1@yahoo.com

Original Letter Available Here:

http://www.tallahassee.com/article/20110804/OPINION02/108040306/Letters-editor

Palm Beach Post: Cuts at nursing homes: Local centers have options, say they won’t reduce staff

By Stacey Singer and Toni-Ann Miller

July 1, 2011

Starting this month, Florida’s 70,000 nursing home residents could find fewer nurses at their bedside after the Florida Legislature voted to lower the homes’ minimum staffing standard by about 8 percent to help them absorb another round of Medicaid budget cuts.

The change means that nursing home patients will be assured an average of just 3.6 hours a day of contact with either a registered nurse, licensed practical nurse or certified nursing assistant, a reduction of about 18 minutes per patient per day.

An estimated 3,000 to 3,500 nurses could lose their jobs statewide as nursing homes shed staff, according to some estimates.

Three out of four seniors in long-term nursing home care have dementia or Alzheimer’s disease and need help with basic needs such as eating and drinking.

Jack McRay, advocacy manager for AARP Florida, predicted that malnutrition, dehydration, falls, bedsores and life-threatening blood infections in nursing homes will increase as nurses become tougher to find.

“You don’t take the nursing out of nursing homes,” McRay said. “We think it was very shortsighted on the part of the legislature.”

The major policy change was inserted into an eleventh-hour budget conforming bill, apparently to mute public input, he said.

“It was published the night before the legislature was adjourned, so it was an up-or-down vote and there was no hearing on this standard,” McRay said.

Medicaid budget cuts are trimming 6.5 percent from nursing homes’ already below-cost reimbursement rates, nursing home representatives said.

In Palm Beach County, 51 nursing homes will lose a combined $13 million because of the cuts, according to the Florida Health Care Association, the long-term care industry’s trade group in Tallahassee.

The Morse Geriatric Center has more than 60 percent of its residents on Medicaid and stands to lose more than $850,000 from the state budget cuts in 2011-2012, the trade group reported.

The suburban West Palm Beach center is a nonprofit that receives some community donations. It will seek savings in food service, vendor contracts and possibly employee raises before cutting staff, CEO Keith Myers said.

“I refuse to cut our front line staff,” Myers said.

The Palm Beach County Health Care District’s public nursing home, the Edward J. Healey Rehabilitation and Nursing Center, has about 70 percent of its residents on Medicaid, said agency spokeswoman Robin Kish. The Healey Center will lose about $460,000 in reimbursements this fiscal year, she said. Because it’s taxpayer-supported, it won’t cut staff, either.

But that won’t be an option in most places.

Statewide, an estimated 40 percent of Florida nursing homes would have operated at a loss in 2011-2012 without the flexibility to cut professional staff, the Florida Health Care Association warned.

The association tried throughout the legislative session to prevent another year of drastic budget cuts to Medicaid’s nursing home rates, said reimbursement director Tony Marshall. Ultimately, the state chose to balance its budget by taking $187 million from Medicaid’s nursing homes, Marshall said.

“We agree that better staffing leads to better care,” Marshall said. “You can’t staff if you don’t have the adequate funding.”

He said the 3.6-hour standard was determined with the help of a state-commissioned University of South Florida study in 2009. The study found that better staffing requirements passed in 2002 had significantly reduced problems at nursing homes, including lawsuits. The standard rose through the years to 3.9 hours minimum, but most of the benefits had been achieved by the time the standard had reached 3.6 hours, Marshall said.

The state average by 2007 exceeded four hours of nurse care per patient per day, above the national average. But those averages are far below what several studies have said is necessary.

Most studies have shown that patients do better in homes with a greater mix of registered nurses. The Institute of Medicine and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services have said the ideal level of care in nursing homes is 45 minutes of registered nurse staffing per resident per day.

In 2007, Florida nursing home patients’ contact with registered nurses averaged 16.2 minutes a day. Here, staffers were more likely to be nurse assistants, whose pay averaged $11.73 an hour in 2007, compared with $26.19 an hour for registered nurses.

AARP is encouraging nursing home caregivers to sign its petition insisting that the homes commit to maintaining their nurse staffing. About 3,000 caregivers have signed it so far, McRay said.

Marshall said the average state nursing home is surviving on a profit margin of just 4 percent to 6 percent, making AARP’s demands unrealistic.

“It’s unfortunate that this is the route that had to be chosen” to reduce Florida’s budget deficit, Marshall said. “We will be back to the legislature to try to close that gap next year.”

Health News Florida: Nursing home staffing level drops today

By Brittany Davis

July 1, 2011

Nursing home residents may have less face time with their caregivers after a law takes effect today that revises minimum staffing levels.

The law is part of an effort to help nursing homes deal with the $187.5 million in Medicaid cuts outlined in the state’s budget.

Nursing home residents will be entitled to 3.6 hours of direct care per day, down from 3.9.

The state requires 2.5 of those hours to be from a certified nurse, down from the current requirement of 2.7 hours. In 2007, the Legislature passed a law requiring 2.9 hours of care.

Sen. Joe Negron, who sponsored the bill, said the move could save the nursing home industry about $40 million per year, allowing them more flexibility to deal with budget cuts. Nursing homes will lose about 7 percent of their budgets.

“We were requiring these nursing homes to meet this standard, but we weren’t giving them the money to do it,” he said. “Some of these nursing homes are barely breaking even.”

Many states have no minimum staffing ratios, Negron added.

Some nursing homes may choose to offer more than the minimum hours of care, but many rely heavily on Medicaid and have already announced staff reductions as a result of the lowered requirement, said Dale Ewart, vice president of healthcare union 1199 SEIU.

Ewart said that union caregivers delivered petitions to the administrations of 41 nursing homes last week, urging them to maintain their staffing levels.

Medicaid pays for 61 percent of the total billable days in nursing homes, Medicare pays for 19 percent and the remaining 20 percent is paid for through private sources such as insurance or residents’ personal funds, according to data from the Agency for Healthcare Administration.

Cloreta Morgan, who has worked at Unity Health and Rehabilitation Center in Miami for 38 years, said the nursing home laid-off 23 staff members in light of the lowered requirements. Her job was spared because of her seniority, she said.

“We submitted a petition asking them to ignore the changes to the law, but administration never addressed it with us,” she said.

Unity Health and Rehabilitation Center did not respond to calls from a Health News Florida reporter.

Ralph Marrinson, president of Senior Care Residences in Fort Lauderdale, said most nursing homes have no choice but to cut back on staff, but that he is looking for ways to keep care consistent by decreasing paperwork and other inefficiencies that stand in the way of bedside time.

“Everyone is going back in and digging into their budget and trying to find a way to save without impacting the level of care,” he said.

Florida first implemented minimum staffing levels in nursing homes in 2001. One 2002-2007 study, funded by the Agency for Healthcare Administration and carried about by the University of South Florida, found that higher staffing levels mean fewer falls and bedsores for residents.

Face-time with caregivers also helps patients stay mentally active, said Dr. Robert Schwartz, professor and chair of the University of Miami’s Department of Family Medicine and Community Health.

“I can understand the state in terms of looking for areas to cut their budget, but as a physician it’s tough to justify that as an area that should be cut,” he said.