BY ZACHARY FAGENSON AND LYNSEY WEATHERSPOON 17 AUGUST 2020

No place seems safe for Elonda English, not even her car.

Just after sunrise on a recent Wednesday she emerged from an overnight shift at the Lake Mary Health and Rehabilitation Center, a nursing home about 30 minutes north of Orlando, wearing a surgical mask and a condensation-fogged face shield.

In a parking lot surrounded by oak trees with billowing Spanish moss she pulled out what she calls her COVID bag, stuffed with an arsenal of sanitizers, from the trunk of her silver Kia Forte.

After slipping off her sneakers and spraying them down with disinfectant, she misted her feet, sandals, and her still-clothed body as she got into her car and pulled off her mask, waving at other masked nurses arriving for the day shift.

At her home in a small gated development of beige and dark green stucco townhouses and apartments, she’s greeted by a plaque outside of her front door.

The words of Psalm 91 are printed on a posterboard with an American flag, renamed the “2020 COVID Prayer of Protection.”

Inside, her 50-year-old mother Evelena Campbell, who drives a bus for another nearby nursing home, has been quarantined for the past week after testing positive for the coronavirus.

English, 35, a certified nursing assistant (CNA), is one of tens of thousands of elder care workers across Florida who for months have shouldered much of the weight and some of the losses of a growing pandemic that lingers across the peninsula, infecting more than a half a million people and killing nearly 9,000 others.

While much of the focus has been on doctors and nurses working in intensive care units, particularly in hard-hit South Florida, nurses caring for the elderly in places like Central Florida, with its massive retiree population, have long struggled for better pay, benefits and staffing levels.

“We are the foundation, and when your foundation has a crack in it you know it’s going to fall,” English told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

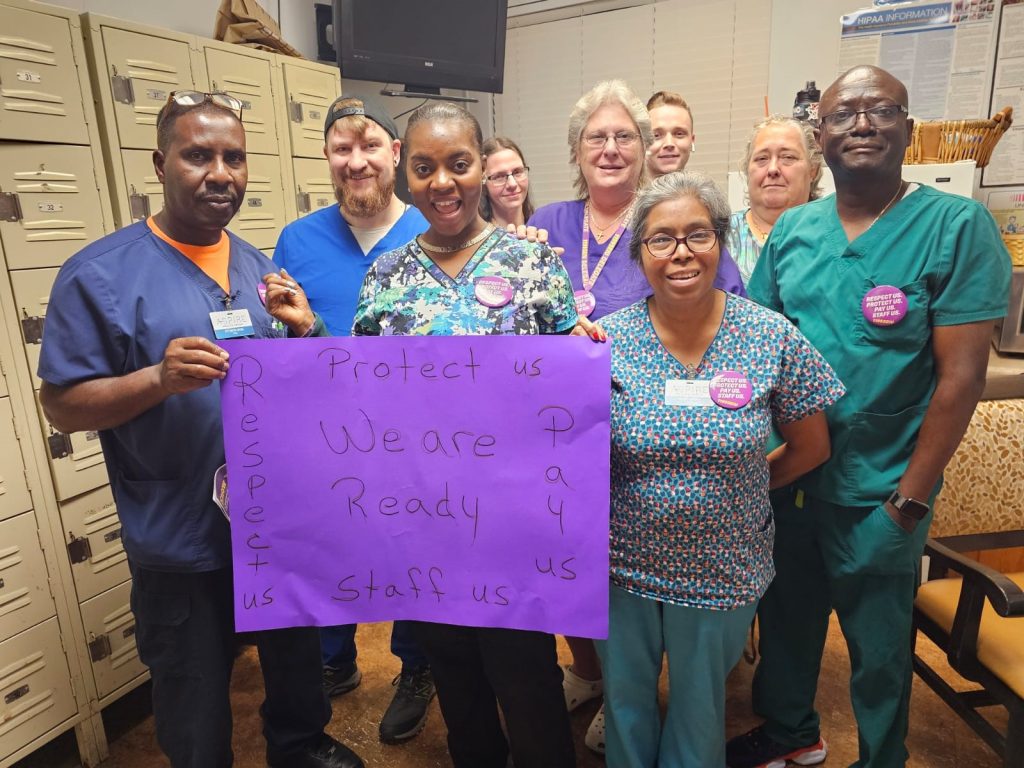

“I would say of the facilities that we represent 95% (of the CNAs) are females and I would say a good 60% of those are African-Americans and 30% are Haitian-American,” said Clara Smith, central Florida regional director for 1199 SEIU United Healthcare Workers East labor union.

In Smith’s region, the union represents about 15,000 workers spread across 76 nursing homes and similar facilities.

About 1,200 of those work for Consulate Health Care, the owner of the Lake Mary facility and the predominant nursing home company in the state.

So far one staff member has tested positive for COVID-19 at the Lady Mary Health center.

The pay across the industry is paltry.

Smith said the starting rate is $10.40 per hour in line with a four-year-old bargaining agreement. Most CNAs in the union make between $11 and $12 per hour. The state’s minimum hourly wage is $8.56, by law.

They’re offered health care insurance, but most don’t take it due to the high cost of premiums and deductibles.

The pandemic exacerbated the pay issues after nurses and other workers began falling sick and were forced to quarantine, sometimes more than once.

In some cases they were told they would have to use their vacation time, and the union is fighting with many companies for added hazard pay.

Smith said the union was able to file complaints with the federal government’s Occupational Safety and Health Administration and have those orders removed and the facility administrators replaced, but it’s still happening in some places.

Laura Gee, a 65-year-old CNA, who works at the Rosewood Health and Rehabilitation Center on the outskirts of Orlando, had to take time off work after experiencing symptoms similar to those in people suffering from COVID-19.

Gee was quarantined for eight days before testing negative and returning to work.

Prior, she was working up to 75 hours a week, and sometimes 100 after other nurses fell ill and couldn’t work.

Despite the low pay, the danger and the fact that Gee is diabetic and was hospitalized three times before the pandemic with respiratory issues, she said she and other CNAs remain committed to their patients, no matter the situation.

“The higher-up people can be kind of hard on us, we’re tired, we’re drained, we walk around like zombies and it’s only the residents that make us feel appreciated,” said Gee.

“I’m there for my residents and that’s how I keep going. I’m not there to please the administration, the nurses, or the head honchos. I’m there to take care of my residents, to make sure they’re clean and happy and to give them love.”

About one in five Florida residents is a senior aged 65 or older. Statewide there were about 140,000 residents and about 196,000 staff in assisted living facilities and skilled nursing facilities, according to the Florida Department of Health and the Agency for Healthcare Administration.

Of those 5,317 residents and 5,442 staff were positive for COVID-19 as of August 11. Those figures don’t include individuals who either died or recovered from the disease.

Brian Fox, head of the national nursing home watchdog group Families For Better Care, said the tragedy has been years in the making due to a growing trend of investment groups setting their sights on senior care and a failure of state and federal governments to provide adequate testing, guidance and safety equipment for nursing home workers at the onset of the virus.

“The bottom line took precedence over care and quality, and across Florida they scaled back on the one thing that costs them so much and that’s the labor costs,” Fox told the Thomson Reuters Foundation.

A group of university researchers earlier this year released a study examining how private equity firms’ investments in nursing home companies have affected residents and employees.

Funds have been moving aggressively into the space nationwide over the last two decades. In 2004 there were 600 private equity deals for nursing homes. This hit 1,500 in 2019.

Among the findings were that acquisitions associated with private equity firms led to less money being spent on staffing and higher resident density, all leading to a lower quality of care as determined by the government’s five-star rating system for nursing homes.

“We expect that private equity-owned nursing homes would be less prepared in an emergency situation like this,” said lead researcher Atul Gupta, an assistant professor in the department of health care management at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania.

Consulate Health Care, owned by Atlanta-based private equity firm Formation Capital, has in recent years come under fire for everything from poor care leading to patients’ deaths to overcharging government programs for medically unnecessary treatments.

Consulate is the largest nursing home operator in Florida and the sixth largest in the country. Congress in June began investigating it and four other of the nation’s largest, for-profit healthcare providers over its handling over the novel coronavirus.

A statement from Consulate said the company had maintained a “vigilant focus” on protecting patients, staff and families since the onset of COVID-19 and its rates of infection, hospitalizations and deaths were better than national averages.

It had also given iPads to each center for families to stay in touch, provided bonuses to front line caregivers, compassion pay, and paid for COVID testing, among other measures.

“We have remained steadfast in our commitment to care for, and protect, our residents and staff during this unprecedented time and will continue to do so with compassion and vigilance,” the company said in a statement.

At English’s nursing home, she said workers were given disposable face masks at the beginning of the pandemic and told to make them last for 30 days. That dropped to 20 days after the union intervened.

Many are concerned about Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis’ recently announced plans to begin exploring how to reopen the state’s nursing homes to visitors, particularly the families of those residents who have been locked out since early March.

“I think a lot of the family members understand that these are difficult circumstances,” DeSantis said during a coronavirus press conference earlier this month in Jacksonville.

“Clearly they would not want policies to be done that would lead to massive amounts of people in these facilities getting infected. But I think that if you have a way forward, I think that would put a lot of people at ease, knowing that there’s a light at the end of the tunnel.”

Critics, however, are concerned that such a plan, without quick accurate testing, poses a massive risk for the already suffering industry and those living and working in it.

Whether that happens English still has procedures in place to minimize her risk of bringing the virus home from her job, or going out and getting exposed.

She’s constantly sanitizing every surface of her home and all but stopped leaving her house for anything other than the essentials.

“Things just aren’t the same anymore,” she said while in her kitchen preparing food for the workday ahead.

“You can’t enjoy life like you used to, you can’t go to restaurants, and now you almost have to be suspicious of everyone because you don’t know what people are doing and some people don’t even want to wear their mask.”

As she put on her mask she double checked her cooler bag. She brings her own plastic utensils, her own water, and food that won’t need to be reheated.

Even her insulin is sequestered. She packs it with ice into a small vacuum bottle before heading out the door with every day looking more and more like an endless unknown.