Reporter: Lauren Sweeney

Workers from Heritage Park Rehabilitation and Healthcare, who wished to remain anonymous, told WINK News that they are not being informed about possible infections of COVID-19 at the facility.

“We are walking into a room, not knowing if that person is positive or negative,” said one staff member.

According to a report published Wednesday from the Florida Department of Health, 26 staff at the facility are currently positive with COVID-19.

The same report showed that 13 residents with the virus were “transferred out” and no one residing at the Heritage Park facility in Fort Myers currently has the virus.

However, staff members told WINK News they fear that the case count is not accurate because the facility is no longer testing residents.

“At one point in time when they had a COVID-19 isolation unit, they were taking protocols to control spread by keeping it with the same staff,” said another staff member who also wished to remain anonymous.

In July, workers said management boasted the facility was “COVID-Free”.

But, a WINK News analysis of archived Department of Health case reports found a discrepancy.

From June 30, through July 7, the facility did not provide any updated case numbers to the Department of Health. Each day in that timeframe lists the reporting information from June 30.

Then, on July 9, when updated information is available, the number of positive residents dropped from 28 to 1.

The Department of Health and AHCA did not address questions about the apparent discrepancies found in case reporting.

AHCA said facilities report their own COVID-19 case information but failed to address follow up questions.

An executive order signed by Governor Ron Desantis in June required bi-weekly COVID-19 testing of all nursing home staff statewide.

The state does not require facilities to test residents routinely.

These recent worker concerns come months after the nation’s largest healthcare workers union filed complaints with state and federal regulators about safety concerns at Heritage Park.

WINK News first reported in May worker concerns regarding protective equipment and notification about patient’s COVID-19 status.

A worker in May said the staff only found out about the facility’s positive residents after looking at the Department of Health data online.

“I don’t like watching people get sick I don’t like watching people die,” said Damien Dixon, a resident at Heritage Park who said he had to sneak away from administrators to call WINK News.

According to Dixon, the quality of patient care at the facility has declined since the beginning of the pandemic.

In late May, the Agency for Healthcare administration found several deficiencies at Heritage Park related to COVID-19.

MORE: Find COVID-19 cases at long-term care facilities

Masks, gowns and other protective equipment were not readily available according to the report.

Inspectors also found two isolation rooms without signage to alert staff that it was isolation room or provide any information about why the patient was isolated.

COVID-19 positive residents are supposed to be in isolation rooms according to CDC guidelines.

In July, inspectors returned to find, “The facility failed to thoroughly evaluate resident’s needs and update the facility assessment to identify resources to provide necessary care and services to residents affected with the Novel COVID-19.”

Heritage Park reported to AHCA after the May and June inspections, that it would take corrective action.

AHCA has not answered WINK News inquiries on whether or not the facility is now in compliance.

Workers claim the problems still exist, and administrators are only interested in clearing the deficiencies so they can admit patients again.

“We can’t admit anybody because we have to clear our tags, because when you don’t admit anybody, that means the building’s not making any money,” said a staff member.

Consulate Healthcare, the company that owns Heritage Park, did not respond to several inquiries from WINK News.

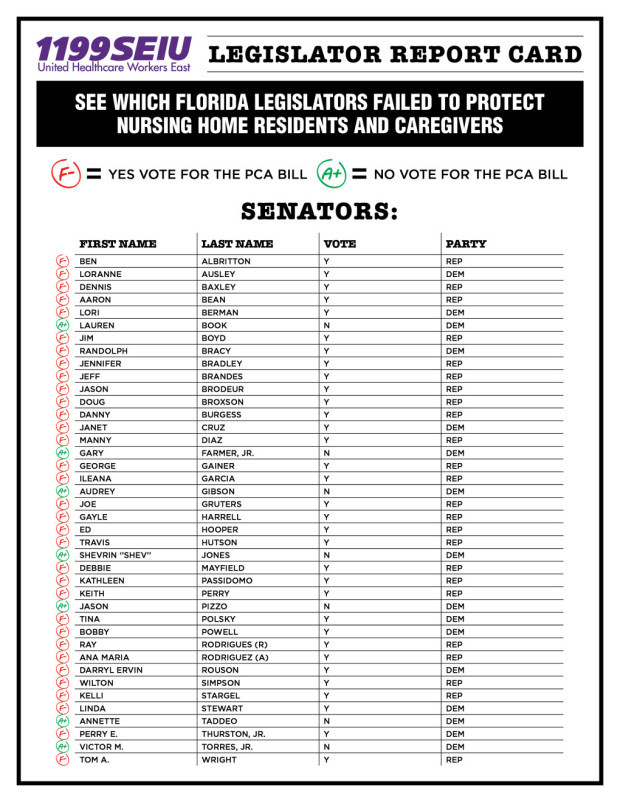

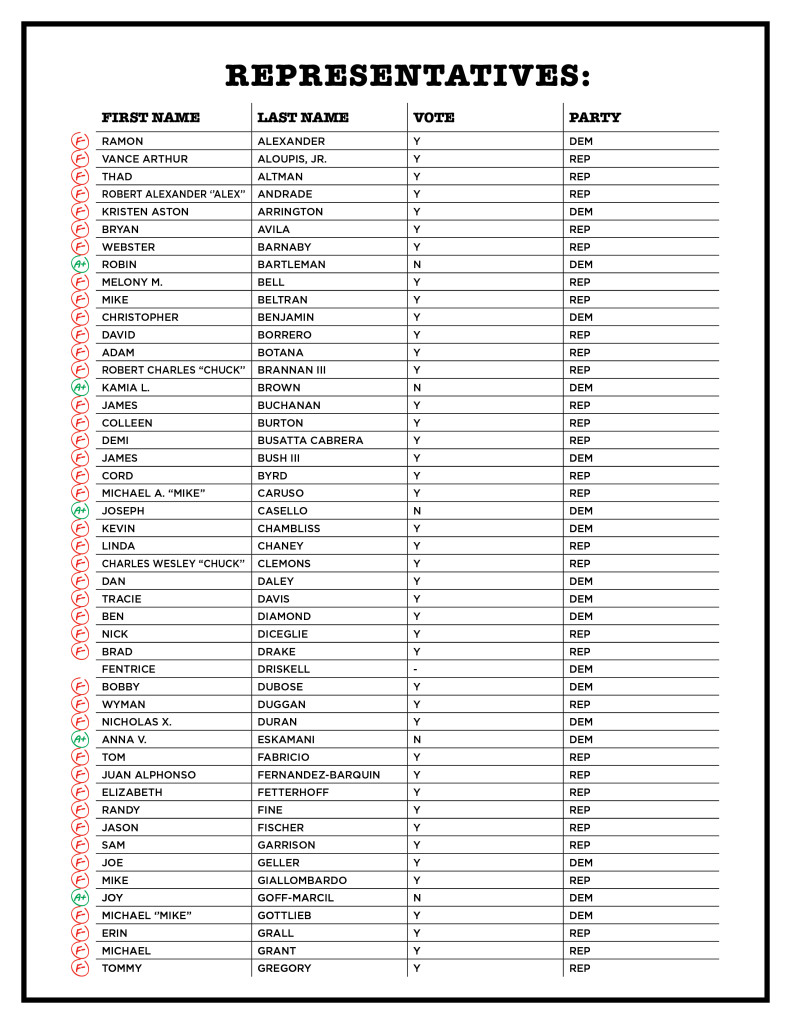

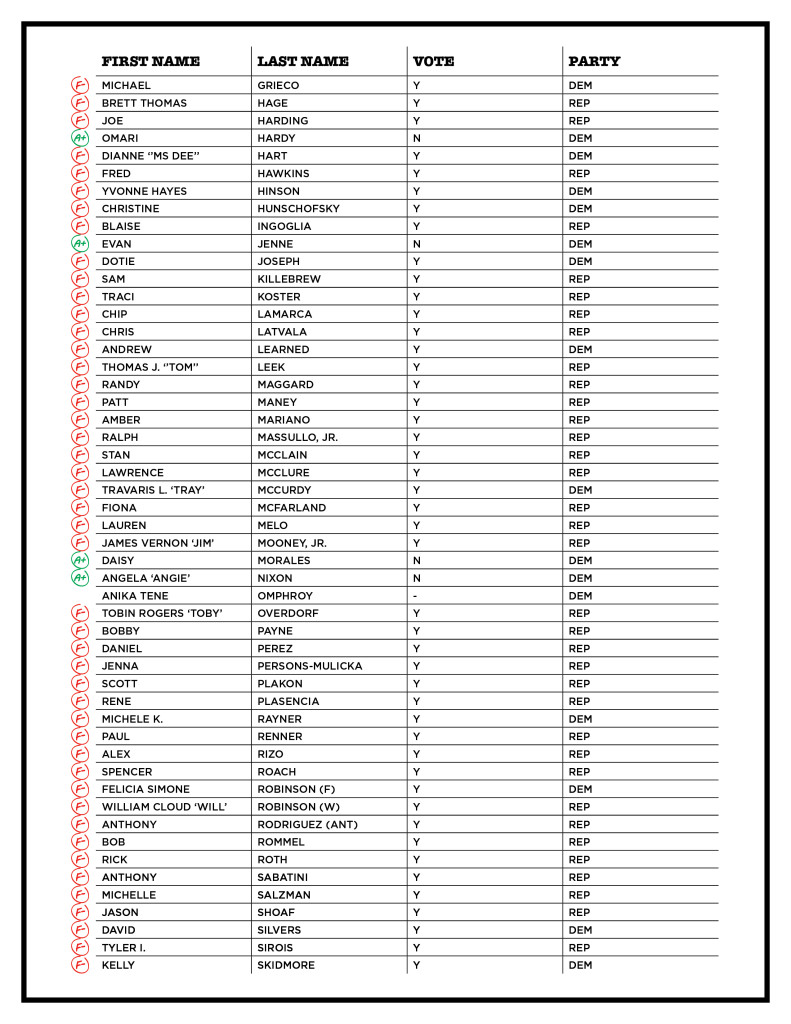

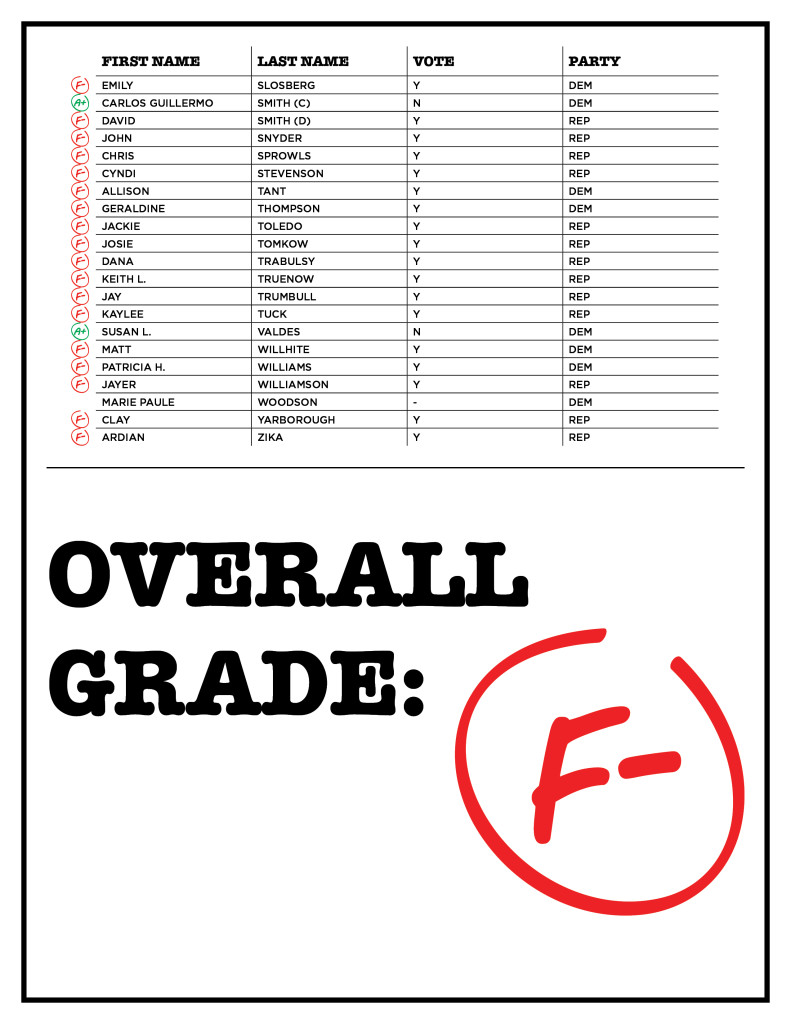

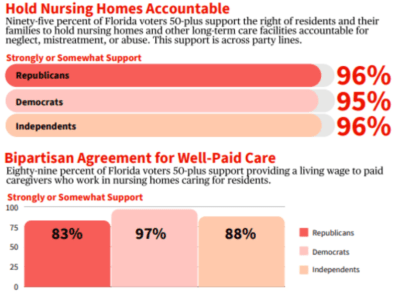

“It’s unconscionable that nursing home workers who put themselves at risk every day during this pandemic to care for our loved ones don’t make enough to provide for their own families,” said Roxey Nelson, Vice President and Director of Politics and Strategic Campaigns at 1199SEIU, the largest healthcare union in Florida. “This has a ripple effect because low wages lead to high turnover which impacts staffing levels and ultimately the quality of care.”

“It’s unconscionable that nursing home workers who put themselves at risk every day during this pandemic to care for our loved ones don’t make enough to provide for their own families,” said Roxey Nelson, Vice President and Director of Politics and Strategic Campaigns at 1199SEIU, the largest healthcare union in Florida. “This has a ripple effect because low wages lead to high turnover which impacts staffing levels and ultimately the quality of care.”